The Lower-Deck of the Royal Navy 1900-1939: Invergordon in Perspective

The Royal Navy (never merely the ‘British’ Navy) has historically been a bastion of deep dyed conservatism, reaching down from the Board of Admiralty to the most lowly seaman and stoker on the mess deck. And yet, during the first thirty years of the last century, it gave rise to a movement for the reform of conditions conducted by the lower-deck ratings themselves. This was a remarkable development in a disciplined service where ratings were denied the right to collective representation. The Naval Discipline Act, always prominently displayed in ships and naval establishments, was a truly fearsome document setting out harsh punishments for action that, in civilian life, would not be seen as an offence. Yet in spite of this deterrent, the organisations the lower deck established to pursue their campaign came close to resembling trade unions which were completely forbidden. This movement of naval ratings is now long forgotten and, even in its heyday its existence barely registered outside the ranks of serving sailors and the naval communities from where they came. This book aims set the record straight and to establish for the movement a rightful place in naval social history.

That service conditions of the time – unchanged for generations – were such as to warrant a protracted campaign for reform is little known. Yet a long list of ‘disabilities’ provided a continuing focus for lower-deck organisation and agitation. At the dawn of the twentieth century, close to 100 men were deserting from the Navy each month because of the harshness of lower-deck life. Thirty years on, with a substantial record of lower deck reforms already achieved, upwards of 12,000 men of the Atlantic Fleet still found it necessary to mutiny – effectively declaring a ‘strike’ – in protest over a drastic cut in pay.

The intervening years witnessed a long record of direct protest action on individual ships over harsh discipline. As an instance, lower-deck disaffection would frequently manifest itself in men throwing gun sights overboard – so impeding gunnery drill and affecting the consequent record of the ship’s gunnery performance – as a way of drawing the attention of the press and public to the oppressive regime prevailing. Equally it might take the form of mass leave-breaking in circumstances where men believed they had been driven too hard or denied leave.

In the years 1900 to 1914 there was at least one naval court martial annually in which a total of 75 ratings were charged as ring leaders, found guilty of mutinous behaviour and punished with custodial sentences – involving as much as two years’ hard labour and then followed by a dishonourable discharge. Such cases were meant to serve as a warning to others. But beyond such high-profile cases, there was always scope for the Navy to get rid of perceived trouble-makers with less fuss by simply marking their parchment papers ‘Services No Longer Required’. Men ‘SNLR’d’ in these circumstances were then unceremoniously drummed out of the service without explanation or redress.

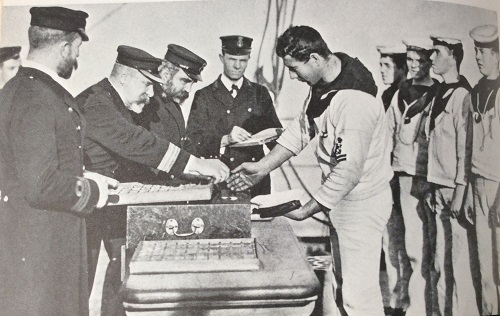

To progress beyond the need for such direct action, the lower deck formed ‘benefit societies’ – quasi-trade unions; organised a system of frequent petitions to the Admiralty; maintained a vigorous lower-deck press to publicise grievances; lobbied politicians (again a wholly unlawful act) – and even established personal contact with higher-ranking former naval officers sympathetic to their cause. At their peak influence, lower-deck benefit societies managed to secure for themselves a de facto role within a formal consultative committee structure that periodically examined proposals for improved conditions.

Famously, in 1917-18 sailors of the Russian Baltic Fleet and the German High Seas Fleet had mutinied and in so doing helped spark off a train of events which led, in both countries, to revolution. No such development occurred in Britain, though the lower-deck reform movement was at its peak in 1919-20. Why the difference? Certainly there were dissimilarities in the circumstances of the lower deck as compared with their Russian and German counterparts. The latter were not volunteers, as were British seamen, they were subject to a much more autocratic system of command, and their conditions were far worse than those in the Royal Navy. But it would be wrong to think that there was never any likelihood of British sailors rebelling too.

Indeed there was considerable unrest in the Royal Navy in the final stages of WW1 and the immediate post-war period, with some 110 ratings court martialled (87 Royal Marines serving in post-revolutionary Russia in one instance alone) charged with serious disciplinary offences. They were handed custodial sentences of up to five years’ hard labour, and thirteen of them were sentenced to death before the punishment was commuted. What prevented it from boiling over – hence making the crucial difference from the Russian and German navies – was that the Royal Navy bent its own rules and allowed the ratings a controlled outlet for venting their grievances. Moreover, such improvements in conditions as had taken place in the previous decade or so were almost entirely the result of lower-deck ‘representations’. In other words, the system had a built-in safety valve, which, however limited, ad hoc and unsatisfactory, gave ratings some hope of amelioration.

In view of this, it is ironic that that just twelve years later, in a political climate far less volatile than that of 1919, the Royal Navy was shaken to the core by the mutiny of the Atlantic Fleet at Invergordon. How was it that the British government and the Admiralty which had managed to negotiate a difficult and tense period of lower-deck unrest in 1919-20, blundered into a situation where men were forced to protest so dramatically in 1931? The answer surely lies in the fact that the lower-deck reform movement began to fade in the 1920s, and feeling less pressure to reach accommodation, the Admiralty allowed the mechanisms that had provided the safety valve to fall into abeyance.

Ultimately, the mutiny at Invergordon has to be understood in the context of the long history of relations between lower deck and Admiralty, in the interplay of forces between an active campaign for reform, the growing expectations of ratings that they were entitled to have their collective views ‘heard’, and the naval authorities’ partial attempts to accommodate themselves to these pressures without relinquishing control of the lower deck. In its preparedness to make some concessions when its back was to the wall, only to withdraw them when the climate turned more favourable, the Admiralty was demonstrating the same sort of guile that had already become second nature to employers confronted by an awakening industrial working class.

Share on

Facebook

Share on

Facebook Share on Twitter

Share on Twitter Share on

LinkedIn

Share on

LinkedIn Share on

WhatsApp

Share on

WhatsApp Copy

link

Copy

link