The Stoker, the Gunnery Lieutenant and Issues of Naval Discipline around the 1906 Portsmouth Barracks Mutiny

On a summer’s day in 1933, a man in his fifties - down on his luck and ‘on the tramp’ in search of work - knocked on the door of an upmarket Regency terraced dwelling in West London barely a stone’s throw from Kensington Palace. He was a former naval rating. Whether or not he’d been tipped off locally that this was the home of a naval officer and so a possible ‘soft touch’, his pitch on the doorstep was the standard one of ex-naval ratings: he was an all-round ‘handyman’ and wanted work.

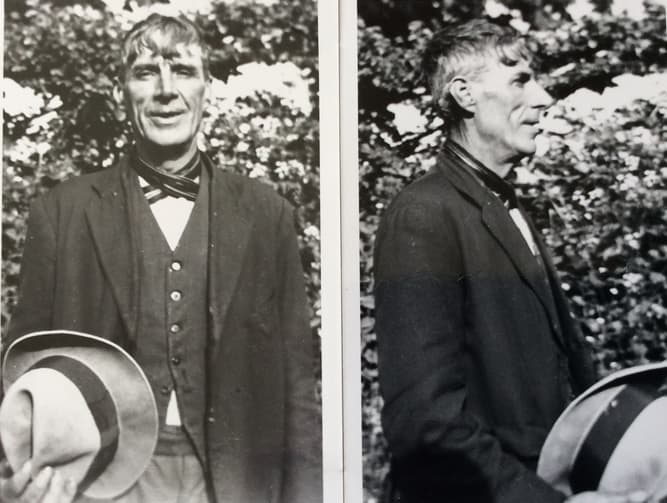

The householder was Lt Commander Charles Drage, recently retired from active service. Naturally gregarious, Drage invited the caller in and was soon able to situate him when he began to hear his story. The man looking for work was former Stoker First Class Edwin Moody, a name that had become part of naval folklore among subsequent generations of lower deck ratings. For he was the man at the centre of the famous ‘On the Knee’ mutiny at Portsmouth Naval Barracks in November 1906.

As a keen amateur photographer, Drage had him pose and so captured him as he appeared nearly 30 years on from that famous event. Over the years the legend around Moody had been layered by countless repetition. In the 1970s, forty years after Moody’s photograph was taken, when I was researching my history of the Lower Deck Movement of the early years of the 20th century I heard from a fair number of ex-ratings claiming - altogether improbably - to have witnessed the event for which Moody had become famous, albeit that some of them now interwove it in a garbled account of imagined events associated with the 1931 Invergordon Mutiny.

The Events at Portsmouth Barracks, November 4-5, 1906

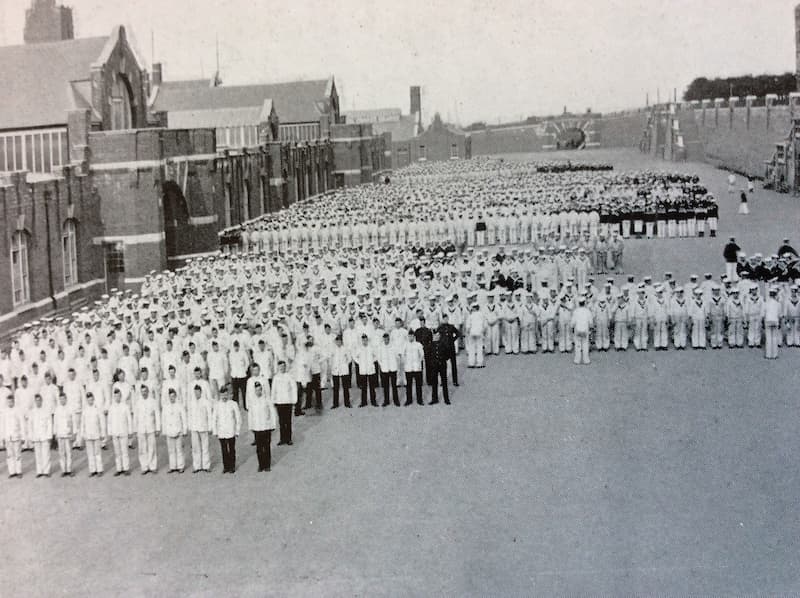

The bare facts of the 1906 mutiny are that on Sunday November 4th at Evening Quarters, when men were routinely mustered on the parade ground in the late afternoon, the stokers – some 390 of whom were in Barracks that afternoon - were disorderly. After being kept standing for longer than usual in cold weather, some of them broke ranks and ran for cover when a heavy shower came on. All the stokers were summoned to muster again in the gym afterwards for a dressing down. Addressing them, the senior gunnery officer, Lieutenant Bernard St George Collard, ordered them ‘On the Knee’, a command that was sometimes given in gunnery training when men were being lectured on a technical point but nevertheless an order unfamiliar to stokers. Many of them initially refused, shouted ‘no’ ‘no’, ‘don’t obey’, jeered those who did go down and only complied with great reluctance when ordered a second time and threatened with severe punishment.

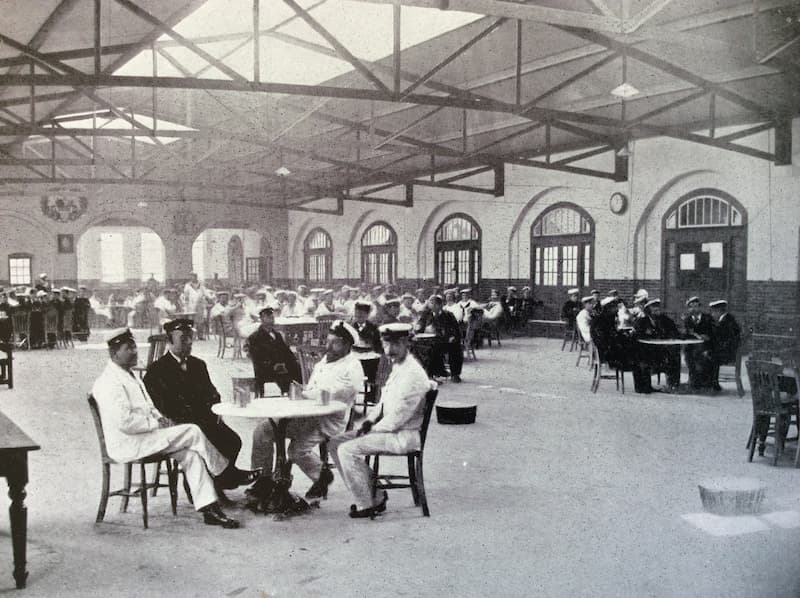

There was much disgruntlement among stokers and later that evening as the canteen was closing one of a departing a group shouted ‘on your knees’ at which men began to smash glasses. Twenty or so were arrested and taken to the guardhouse. Others then tried to rush the Barracks gate in order to cross the road and protest about Collard outside the officers’ quarters. Locked gates prevented the exodus. Meanwhile general disorder prevailed for several hours within the Barracks, a large number of men were placed under arrest, and ratings returning from weekend leave were locked out and forced to find accommodation in Portsmouth that night.

Throughout the following day normal routine was followed, but in the evening there was again a serious disturbance in the canteen with glasses and windows smashed and general riotous behaviour in the Barracks. A large crowd of over a thousand made up of locals and including ex-naval ratings gathered outside the locked gates and began to riot, calling for ‘justice for stokers’, throwing stones and breaking windows in the Barracks and the officers’ quarters. In addition to the local police - including mounted officers - a detachment of 100 armed Royal Marines was called out from Eastney Barracks and several ships in harbour and it was not until the early hours of the morning that they were able to drive the protesters away from the streets adjoining the Barracks.

Meanwhile within the Barracks all men were ordered to assemble on the parade ground where Commodore Stopford and Commander Drury-Lowe made unavailing efforts to restore order and establish what the ratings’ concerns were. Large numbers of men continued to refuse orders, the Commodore was jostled, and in the course of this confusion Moody was marched forward by Stoker Petty Officers to explain to the Commodore what was exercising the stokers.

The upshot of all this was that 11 stokers were court martialed the following month. All but two of them were found guilty and given severe custodial sentences. Afterwards Lieutenant Collard was also court martialed but though found partially at fault he was merely reprimanded.

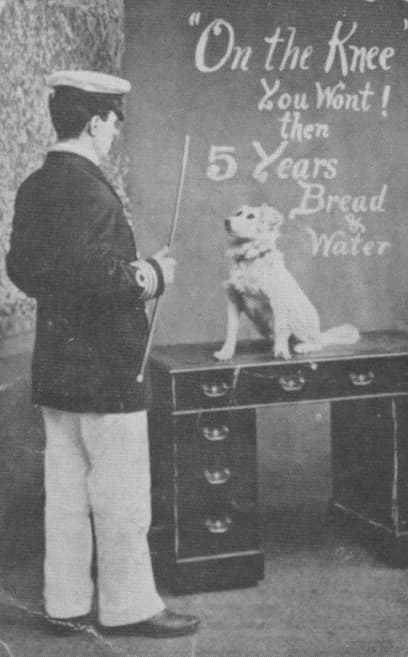

The Origins of the Mutiny: the Acton Affair

The roots of the mutiny went back a year to an episode the previous November when, as punishment for a breach of discipline, the same officer - Lieutenant Collard, who had only joined the Barracks a few days earlier – punished a young man, Stoker Acton, by ordering him ‘On the Knee’. His offence was to have responded ‘Here’ rather than ‘Here Sir’ when being mustered for a stokers’ fire party. Witnesses claimed Collard’s actual words were ‘On your knee you dirty dog and learn your manners’. This was this version that was believed on the lower deck. It later became the subject of newspaper cartoons and picture postcards.

Acton was urged by fellow stokers to seek legal advice from a Portsmouth solicitor. A friend of his later testified that on Acton’s behalf he went ashore to discuss the case with a local solicitor. There was talk of Acton seeking financial compensation in the civil courts and on the lower deck it was assumed this lay behind a subsequent change of heart by Collard. He apologised to Acton in front of witnesses and told him his name would not appear in the Commander’s Report.

Acton himself was quickly drafted to a ship in the Channel Fleet and within a few months he deserted – never to be recovered by the Navy. Other men who were present at the episode were also drafted away from Barracks so that when eyewitness accounts of what happed were required 12 months later they were hard to come by. The point is that the naval authorities only became aware of Collard’s use of this questionable punishment a year later when the cause of the 1906 Barracks riot was under investigation.

The Navy’s Culture of Punishment

The stokers’ reaction to this novel form of punishment is best judged in the context of how they regarded the Navy’s disciplinary regime more generally. Summary punishments in the early years of the 20th century were numerous and irksome, many seemingly intended to degrade and humiliate. In every single year from 1902 to 1911 more summary punishments were handed down than there were actually men on the lower deck. Every Petty Officer and rating stood a better than even chance of being punished at least once a year. It was almost as though the Service went out of its way to manufacture defaulters who could be punished by the Captain without any right of a trial. A naval captain ran his ship largely as he wanted. Where summary punishment was concerned there was no such thing as universal naval discipline, only the discipline of this or that ship. Ratings never knew where they stood: as the lower deck saying had it, ‘Another ship, another Navy’.

Acting on his own authority, a commanding officer could imprison men for up to three months; place a man in solitary confinement for up to two weeks; deprive him of his leave; stop him from receiving rum, stop him smoking, order him to do extra work and stop his pay. Unquestionably the most detested summary punishment was known as ‘10 A’. It involved the defaulter being forced to turn out each morning an hour before other men, eat his meals and drink his cocoa on an exposed part of the upper deck under the watch of a sentry, and between 8.30pm and 10pm to stand on the upper deck facing the bulkhead like a child in disgrace. This commonplace punishment might last up to 14 days during which time the man’s rum would be stopped and he would not be allowed to smoke.

The sort of offences for which such punishments were often awarded included drunkenness, leave-breaking, negligent performance of duty, playing cards (with the routine assumption that this involved gambling which was forbidden), being improperly dressed and using profane language.

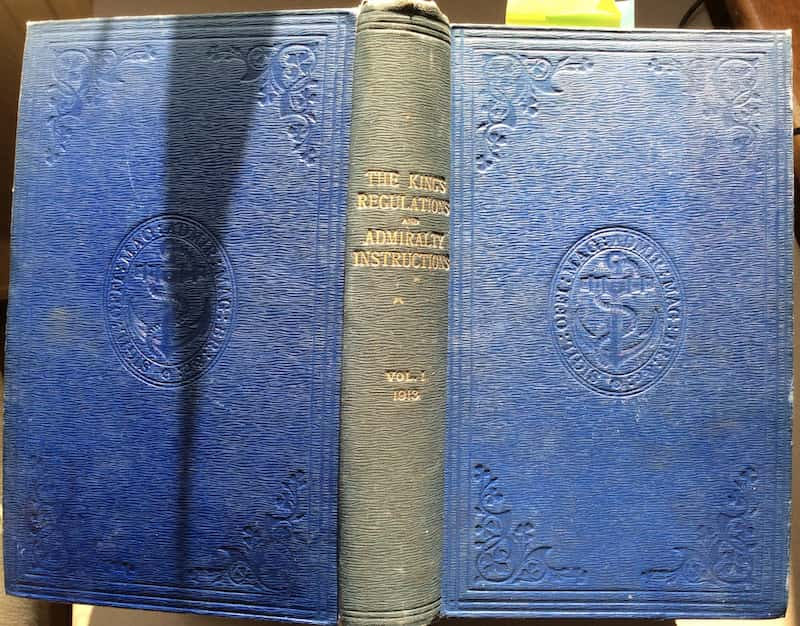

The mentality of officialdom on matters of discipline was well demonstrated in its attitude to men who tried to find out what their legal rights were. King's Regulations and Admiralty Instructions (900 pages long) laid down detailed rules for officers and men. To discover precisely what they contained, a man would normally need to ask the Captain’s permission to consult them. But this was the surest was way of being branded a ‘sea lawyer’.

Yet even King’s Regulations didn’t cover all the possible disciplinary mantraps. Many captains also adopted another list of unofficial regulations. These were contained in A Battleship Commander’s Order Book, a compilation of various ship routines in force in the Mediterranean Fleet in the late 1890s that became widely used though it had no official standing. It was geared to achieving a high degree of spit and polish as an end in itself with a never-ending list of do’s and don’ts of the most trivial kind. It forbade such things as men going over the lower booms with their trousers turned up, leaning on the forecastle rails, not keeping towels and soap in their white hat covers; not having the letter “S” of HMS Royal Sovereign on their cap ribbon positioned precisely over the nose, and on and on ad infinitum.

Given this context, for stokers now to hear the command “On the Knee” as a form of admonishment was to encounter yet another capricious form of humiliation. True, this perverse culture of discipline was an entrenched and almost hallowed feature of Naval tradition in the late Victorian era. But now, at the dawn of the Dreadnought age, with the Service embarking on a drive to revolutionise materiel, a parallel development was beginning to manifest itself on the lower deck: a new generation of naval ratings was no longer disposed to accept unquestioningly an ancient approach to discipline quite out of line with the norms in civilian life.

Lionel Yexley and the Lower Deck Reform Movement

A key figure in this was Lionel Yexley, a former rating who founded and edited a new, independent lower-deck monthly magazine, The Fleet, that began publication in 1905. [See Yexley biographical entry] It campaigned for better conditions on the lower deck and began to turn the spotlight on archaic features of naval discipline. Yexley went down to Portsmouth Barracks in June 1906 to investigate after learning of lower-deck complaints of irregularities in the way the canteen was being run.

While there, he picked up vibes of discontent about Collard’s style of discipline and wrote about the developing regime of pinpricks producing a growing number of complaints to the magazine: a couple of officers were said to be the main problem. He obtained an interview with Commodore Stopford who commanded the Barracks but their encounter didn’t go well. Stopford concluded that Yexley was a troublemaker and barred him from further access to the Barracks. Yexley in turn warned him that the eyes of the press were on nefarious practices in the Barracks and that if necessary he was quite capable of arranging to have backbench members of parliament ask questions likely to cause embarrassment. In the issue of The Fleet published a week before the Portsmouth mutiny Yexley again warned of the ‘tensions’ that were evident in the Barracks.

The Courts Martial of the Portsmouth Stokers

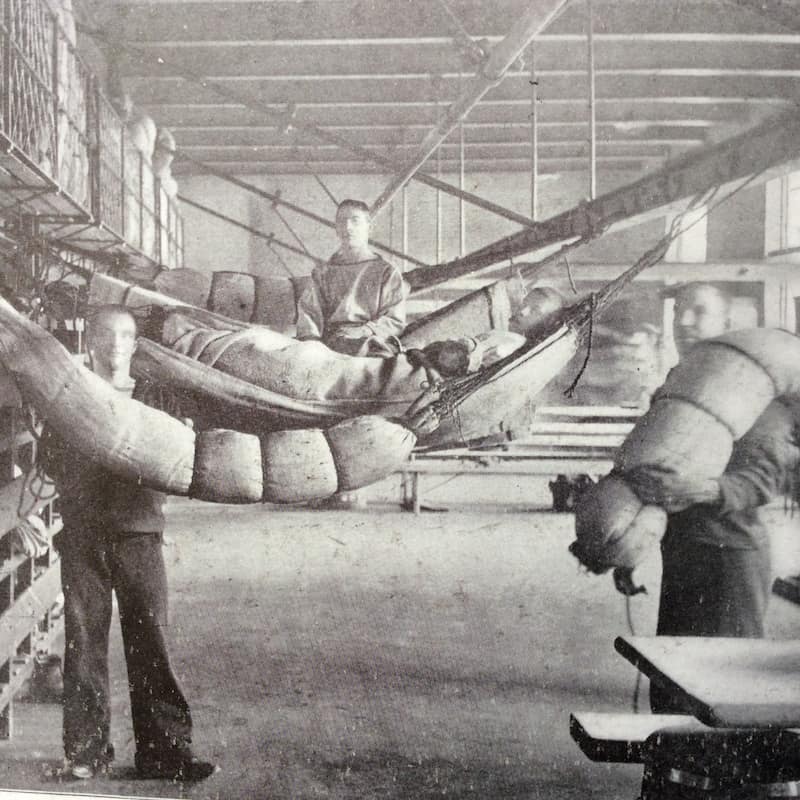

Ahead of the courts martial, a detachment of armed marines was quartered in the Barracks until it was clear that peace had been restored. Hundreds of stokers were quickly drafted to seagoing ships so as to disperse them from Barracks. As a further precaution, the Admiralty gave instructions that in the event of ‘guilty’ verdicts being handed down the prisoners were to be detained on board ships in harbour rather than returned for detention in the Barracks where their presence might cause further rioting. The mutiny and the courts martial dominated the press at home and abroad and held the attention of Parliament for weeks afterwards.

Of concern to the court martial were questions such as whether the mutiny was premeditated; whether the defendants were its ringleaders; if outside forces were at work and, in particular, if it was a product of socialist agitation? In parliament it was suggested that Labour campaigning in the naval ports during the 1906 General Election where leaflets circulated at meetings of servicemen might have radicalised ratings.

But at the courts martial no evidence was adduced that the mutiny was premeditated, clearly no one had orchestrated the chaotic scenes inside and outside the Barracks or served as leader in any meaningful sense. And the notion of outside political agitation as a causal factor simply reflected the reactionary mind-set of people who had difficulty with the idea that servicemen in uniform still had civil rights and were entitled to participate in the democratic political process. The issue of whether naval practices were oppressive and likely to cause a breakdown in discipline was incidental and not a matter for the court martial.

Moody’s Defence

At his trial Moody was formally charged with causing a mutinous assembly and inciting others to join in on November 4 and 5. When he asked more specifically why he had been arrested the court prosecutor told him: ‘you were arrested with many others for disobedience to orders in not going to your room when ordered, for riotous conduct, or for being out of your hammock at an improper time, or for making a noise in your block.’ Somewhere within that catch-all charge comprising matters serious and downright trivial lay Moody’s offence.

Moody’s evidence was in the form of a written statement that had been hurriedly drafted with the help of a prisoner’s friend the night before the court martial began. It was inadvisable for ratings to engage in verbal exchanges with members of the court and so risk appearing disrespectful of a superior officer. So he declined to elaborate further with oral evidence beyond protesting that Collard’s earlier evidence was incomplete in not referring to the Acton affair in 1905 from which all else flowed. Collard was re-called to the stand and was asked to detail those events but he again refused to address the episode as his own court martial was pending.

The thrust of Moody’s statement was that he was little more than an interested spectator during the two nights of rioting in Barracks. He had not been in the canteen on the Sunday night and was in his hammock when the first eruption occurred in the canteen. He only emerged from the stokers’ quarters when the bugle sounded assembly at 10 pm with the rioting already in progress. After reporting himself present on the parade ground, he and others were then marched back to their quarters but were barred from entry by stokers agitating outside. He claimed to have tried to persuade them to turn in but got into an argument and in the course of this he was punched in the mouth. Was this, he asked the court, the action of a ringleader?

Clearly the court martial was unimpressed and preferred to accept a report that Moody had actually said to his fellow stokers: ‘You call yourself men, directly an officer speaks to you, you salutes the fucker and then goes and turns in. Stick together if you are going to.’ Along with scores of other stokers, he had petitioned to see the Commodore about Collard’s controversial command and when advised by Warrant Officer Cox that he would be given the chance had reportedly responded: ‘I’ll ask the bugger some questions’.

He went on to testify that on the following day he had been in the canteen earlier in the evening but had turned in before closing time and was only roused from his hammock when the rioting re-commenced.

He mustered on the parade ground at the sound of the bugle and was prepared to speak to the Commodore if invited. When the Commodore, who was being jostled and jeered by men, asked again what their demands were he was marched forward by Stoker Petty Officers on either side of him. But it was actually one of those Petty Officers who informed the Commodore that the men were asking for an apology from Collard. Moody did not himself address the Commodore and the latter did not recognise Moody as the man who spoke to him.

Moody described how he had then been marched back to his barracks room but, as on the previous night, was prevented from entering by men agitating outside who disapproved of his action and, as The Times reported, ‘tried to lay violent hands on him'. His point was that he was not their leader and had not acted on their behalf. Early the next morning he was arrested.

The court found him guilty of inciting men to join the mutiny though not of causing it. He was ordered to serve five years with hard labour. Of the other defendants, Stoker Day received 18 months, McMichael and Leigh were each given nine months, Fachney and Brown six months, Colclough and Beddard three months, while Stoker Reddish with 42 days had the lightest sentence. In all cases time in prison was with hard labour. Moody’s punishment was intended to be exemplary. It is difficult to escape the conclusion that his previous record of indiscipline must have preceded him and influenced the sentence.

The fact was that as a serviceman, Moody had seen little actual service. He joined up for 12 years in 1903 aged 23 and in his first year forfeited eight days of leave and served 28 days imprisonment for desertion. Two months later he was given 14 days in cells as a summary punishment followed by a further 14 days a month later. For whatever offence these were severe punishments. Cells meant solitary incarceration in a dimly lit space 6ft x 4ft, furnished only with a thick plank hinged to the wall on which to sleep and a table with a bible. The prisoner was placed on reduced diet of water and a few ounces of ship’s biscuit for the first three days and the last three days of his sentence. It was widely recognised that 14 days’ cells was harder than 28 days detention and that it broke all but the toughest of men. Given his previous form it is not hard to imagine how Moody might now be regarded by the court martial as a suitable candidate for further exemplary punishment.

The hard labour awaiting him in a naval prison involved a mixture of working at the treadmill, breaking rocks, picking 2lbs of oakum a day (this involved separating the fibres of tar-covered old rope so that it could be re-used for caulking, an activity that was painful to fingers and thumbs) and two 90-minute stints of shot drill daily. The latter was undoubtedly the severest punishment. It involved standing and bending to lift and move a heavy shot weight from one side to another and then back again. The repeated lifting and carrying of the shot tended to induce an excruciating pain in the loins.

The Trial of Lieutenant Collard

Collard’s court martial followed a week later. He faced two counts of prejudicing good order and discipline by 1) awarding an unauthorised punishment to Stoker Acton and addressing him in abusive terms and 2) making an improper use of the order ‘On the Knee’ to the stokers in the Barracks gym in 1906. Since his evidence had already been used to convict Moody and the other stokers it is hard to see how the court could find against him on both charges now.

In extensive oral evidence he argued that on both occasions he had been faced with acts of indiscipline that could not be ignored and required necessary measures to restore order. This argument was persuasive to the court: maintenance of discipline was essential whatever the circumstances. He complained that he had been subject to unfair attacks in the House of Commons and in the ‘half-penny press’ for things he didn’t do.

He denied having used abusive language to Acton, though Chief Petty Officer James Taylor testified that he had heard Collard tell him, ‘Go down on your knee you dirty dog and learn your manners’. Taylor appeared to have nothing to gain by giving false testimony, but the court martial didn’t believe him. Collard denied ever apologising to Acton though others held that this had been done in the presence of witnesses including the Officer of the Watch. Likewise, suggestions that the threat of civil legal action was what led to Acton’s name being expunged from the Commander’s Report were, he claimed, without foundation.

Collard admitted that since being appointed to the Barracks, he had initiated use of the ‘On the Knee’ command to draw attention to irregularities and had given the order on five occasions in the previous year. It emerged that he had last given it just three days before the riot on November 4 to a class of stokers. The men concerned felt aggrieved at this and afterwards discussed among themselves whether the order was lawful.

On the Acton charge the court found against him for punishing a single individual with the command ‘On the Knee’ given ‘contrary to the ‘custom of the service’. For this he was merely reprimanded. Otherwise, his denial that he used abusive language to Acton was accepted. No penalty was awarded over his handling of the events in the gym that had sparked the 1906 mutiny in the Barracks. The reprimand was but a blip on his record that still allowed him the chance to regain his standing.

The Admiralty’s Assessment

The reporting of the final judgement of the Board of Admiralty to the House of Commons portrayed Collard in sympathetic terms. It said he was entitled to the sympathy of ‘all right-thinking men over the scandalous and unprecedented deluge of calumny and premature criticism to which he was subjected’. His ‘spirited protest against that treatment’ and his ‘manly defence of his conduct’ were especially noted by the Admiralty. Altogether, Collard was portrayed as a man who, ‘in the midst of a certain slackness of discipline...stands out as an officer who tried to do his duty’. His intentions had been excellent – only his methods were ill-judged. Compared with the Admiralty’s negative assessment of his superiors who commanded the Barracks, Collard displayed qualities worthy of admiration.

The Admiralty’s firm view was that Moody’s sentence was not excessive, but the length imposed and the sharp contrast with the lenient way Collard was treated caused an outcry in Parliament and the press. The Humanitarian League passed a resolution protesting at the needless severity of the sentence. Protest meetings were held and a rally in Trafalgar Square. Under pressure from the Liberal government keen to avoid a full scale debate in the House of Commons that would be bad for discipline, the Admiralty reconsidered and decided that there were extenuating circumstances for the men’s action - especially the deep resentment felt over the order ‘On the Knee’. They therefore commuted Moody’s term to three years.

The naval authorities were plainly in a dilemma over the status of the ‘On the Knee’ command. It did not appear in naval manuals and was certainly not part of any disciplinary code. As the wording of the charges against Collard suggested, discussion of the issue was bedevilled by terminological inexactitude - a phrase that Winston Churchill had coined that very year. Rather than simply state unambiguously that it was an unlawful punishment it was variously referred to as a ‘misused drill order’, ‘an improper use of a (lawful?) order’, something that was permissible as a ‘disciplinary measure’ while on the other hand not being permissible as a ‘punishment’. As members of parliament protested, the distinction between the two was somewhat elusive. Such was the fog of words in official discourse. Nevertheless the Admiralty gave instruction that the command was no longer to be used except during drill. To all intents and purposes it now disappeared.

The Case of Commodore Stopford

While there was some sympathy for Collard at the Admiralty, it did not extend to

Commodore Stopford. As the man in charge of the Barracks he found himself in the

spotlight and tried to deflect responsibility onto others for what had gone wrong.

Among those he blamed were his predecessor as commodore who had failed to

correct Collard’s actions, Lionel Yexley, the reform campaigner, and stokers

generally for whom he had clear contempt. He wrote to the Second Sea Lord (the

member of the Board of Admiralty with overall responsibility for personnel) hoping

to exculpate himself. The letter spoke volumes for his proclivity for buck-passing. It

deserves to be quoted at length:

‘There is no doubt that we have lived on a volcano here since November 1905

and I am surprised it did not erupt then. I did not take command until

February 1906 and I feel it a bit hard that if Collard’s eccentricities in the

way of punishments were known by his senior officers that they should not

have informed me of the fact.

There is a very dangerous man called Yexley, editor of The Fleet. He came to

see me one day bringing with him a strong savour of old and recent spirits and

I was polite for a time. But I find he is raising mutiny and discontent and

panders to the lower deck where his principal sale is. He is always trying to

run down the present senior officers in the barracks because I gave orders he

was not to be admitted. He tried to hurt Drury-Lowe (Stopford’s second in

command) over a canteen question which turned into a mare’s nest, but the

question in the House of Commons was prompted by this little reptile. He was

a Chief Yeoman of Signals in the service. We have educated him and taught

him long words and now he spends his time fomenting trouble in an

underhand way.

I considered the Sunday night affair a trivial one. The stokers, having nothing

better to do, nursed a grievance and made fools of themselves at the

instigation of a few deserters from the Army and Socialist vagabonds that

have lately joined the Navy. When I addressed the men on parade on Monday

afternoon I did not know Collard had used the order ‘on the knee’ and did not

know of the occurrence in 1905.

The riot outside was responsible for the riot inside, a put up job by Army

deserters and other riff raff we have as stokers. The stokers were singing

Socialist songs and it was significant that everyone knew the words.’

Overall the Admiralty judged Stopford and his second in command Drury Lowe to have shown a lack of firmness, judgement, tact and discretion. They had not exercised proper control and supervision of the canteen and had failed to correct and censure Collard for his earlier approach to discipline. Both were immediately relieved of their positions. But in the way of the Navy, Stopford was promoted to Rear-Admiral before being forced to retire within two years. Commander Drury-Lowe’s career was not blighted by the episode. He was soon promoted to Captain and retired with the rank of Vice-Admiral 20 years after the mutiny.

Yexley and the Further Reform of Discipline

Stopford’s slurs on Yexley’s character did not hold back his campaigning for reforms. Between 1907 and 1912, aided by having won the personal support of the reforming First Sea Lord, Admiral Sir John Fisher, and through him of Winston Churchill when he became First Lord of the Admiralty in 1911 his constant prodding was in no small part responsible for improvements in feeding arrangements for the lower deck, the simplification of clothing regulations and the first significant increase in ratings’ pay in 50 years. With Churchill at the Admiralty, after a period as Home Secretary in which he had tackled the need for prison reform, Yexley’s crusade to modernise the Navy’s punishment routine began to pay off. In 1911 he published a book, Our Fighting Sea Men, detailing the way punishments were still deeply rooted in the Victorian era and even in Nelson's navy. Churchill responded by setting up a departmental committee under Rear Admiral Frederic Brock to look into the whole issue of summary punishments.

Brock took evidence from nearly 100 officers and men. There was no strong appetite for change among the ranks of naval officers, some of whom argued that naval discipline would suffer if summary punishments were tampered with. Typical of the traditional view was Captain Leveson’s claim in testimony that agitation for reforms was ‘nothing but Socialism, trade unionism and everything else’. He conceded that making a man stand on the upper deck facing the bulwark as part of ‘10 A’ punishment was like putting a child in a corner, but argued that ‘the rating is basically a child and needs to learn to stand still.’

As chairman, Brock was no great reformer and much of his questioning of lower-deck witnesses was aimed at securing an admission that Yexley and The Fleet were at the back of lower deck unrest, asking them, ‘Does Yexley upset people?’ ‘Do the men read The Fleet?’ ‘Do they agree with him?’ Yexley himself appeared before the Committee and spent a whole day giving evidence and elaborating on his claim that naval practices manufactured offences and defaulters. The Portsmouth Barracks mutiny came up for discussion. Brock saw the problem in terms of the type of people stokers tended to be. They were a body of men who had ‘no idea of cleanliness, morality, honesty, or any other thing’. Yexley tried to explain that more than the “On the Knee’ command was responsible – that was just the latest in a long list of arbitrary and humiliating punishments that were bound to breed resentment among the lower deck.

Brock regarded him as an agitator and Yexley recorded that the atmosphere in the committee room was very cool. But he made progress in convincing Brock that some measured changes were necessary. While rejecting the suggestion that there was general discontent on the lower deck, Brock’s subsequent report conceded that discipline generally had diminished and notions of unthinking obedience had been replaced by a tendency to question authority on every possible occasion, making it difficult to uphold naval discipline. A more enlightened approach by officers was thus needed.

Out of the report came an end to the practice of punishing of Petty Officers without their having the right to a court martial and likewise the practice of consequential naval punishments of men who had already been punished for civil offences. Most important of all, Yexley had convinced Brock that a thoroughgoing revision of ‘10 A’ punishment was necessary. In consequence, the hated routine of standing on deck facing the bulkhead and eating meals under the watch of a sentry was soon consigned to the scrap heap. Leave arrangements were simplified so as to reduce the number of offenders breaking their leave. Officers below the rank of Commander were barred from awarding heavy punishment without the approval of their superiors.

Churchill followed up later that year with a series of circular letters pushing the reform agenda further. Cell punishment was to be restricted to no more than three days as a first step to eliminating it altogether. He insisted that the cells he had viewed in Malta were ‘the most disgraceful places he had ever seen’. The power of ships’ police was to be restricted. And so as to reassure men of their legal rights an extra copy of King’s Regulations was to be carried by ships specifically for perusal by ratings. A more relaxed and flexible shipboard routine was to be introduced to lessen the gulf between officers and ratings. It marked the beginning of a new era, with a more intelligent approach to discipline, and significantly 1912 was the first year ever when the number of summary punishments awarded was less than the number of lower-deck ratings.

A Sweet Sequel

There was a sequel to the 1905-06 episodes that would have given old stokers some satisfaction – though it was nearly a quarter of a century in coming. In the intervening years Collard had made his way up the ladder of naval promotions, though without changing his ways. By 1928 he was a Rear-Admiral and second in command of the First Battle Squadron of the Mediterranean Fleet flying his flag on HMS Royal Oak.

He was highly unpopular among the officers of his ship and there was on-going friction between him and his Flag Captain, Kenneth Dewar - a serious minded intellectual type – and Dewar’s first lieutenant, Commander Daniel.

Following a series of episodes in which Collard had shown open contempt for these two officers in front of the crew they submitted letters of complaint. Among other things, Collard had conspicuously failed to return a salute to the Commander when disembarking the ship and, irritated that a ladder was not ready and waiting for him, had said audibly that he was ‘fed up’ with his Flag Captain. In composing his complaint, Daniel had discussed it with other officers in the wardroom and had added hearsay from them about other instances – in naval terms amounting to an act of subversion. In forwarding this letter, Dewar was accused of being complicit in the subversion and of not showing leadership by advising Daniel to tone down the language and content. Indeed he had compounded the situation by writing a separate complaint of his own.

The letters were submitted to Collard who immediately passed them on to his superior commanding the battle squadron who in turn forwarded them to the Commander-in- Chief of the Mediterranean Fleet. The Fleet was about to put to sea for the Navy’s most important annual exercise but since the letters seemed to indicate that discipline in the Royal Oak was collapsing, the C-in-C ordered an immediate court of inquiry and postponement of the the Fleet exercise while it deliberated. The postponement of the Fleet’s departure was big news in Malta and soon the nature of the conflict on the Royal Oak leaked out and became the focus of press attention. The court of inquiry judged that the matters contained in the complaints were exaggerated – a mountain out of a molehill. So Captain Dewar and Commander Daniel were relieved of their posts and sent home. Collard too was ordered to strike his flag.

Dewar and Daniel requested a court martial to clear their names and a month later they were recalled to Gibraltar where their trial took place in the hangar of the aircraft carrier, HMS Ark Royal. Members of the court martial were resplendent in their uniform cocked hats and wearing their ceremonial swords. The world’s press was present in force and had much sport in reporting the centrepiece of the proceedings when Dewar, conducting his own defence, confronted Collard in the witness box.

Most titillating was his questioning Collard about an episode three months earlier in Grand Harbour, Valetta, when the officers of the Royal Oak threw a ball and invited officers’ wives and Malta’s social set on board. People were dancing to the tunes of a Royal Marine band when Collard approached the bandstand, complained loudly that the music was ‘the worst bloody noise I’ve heard in my life’, ordered Commander Daniel to get the Marines off the ship, shook his fist at the Bandmaster and told Daniel ‘I won’t have a bugger like that in the band’. The Marines were dismissed and a jazz band summoned. When the ship’s chaplain tried to intervene, Collard threatened him with a court martial.

Dewar asked Collard in the witness stand if he had called the bandmaster ‘a bugger’. Collard admitted it but wondered ‘Who had called the bugger a bandmaster’. To reporters and cartoonists it was manna from heaven. The ‘Jazz that Jarred the British Navy’ was the headline in one American newspaper. The Royal Navy was made a laughing stock. King George V was deeply concerned and summoned the First Lord of the Admiralty for an explanation. Small wonder that the First Lord refused requests in the House of Commons to publish the full 500 page transcript of the trial.

As the sacrificial victims that the Service demanded, Dewar and Daniel were reprimanded which soon brought their naval careers to an end. But Collard too was forced to retire: the Navy had had enough of him. And for that at least old stokers might have judged that in a small way justice was finally done.

A Century On

Almost 100 years on from the trial of the 11 stokers and 75 years since Captain Dewar and Commander Daniel were hung out to dry the Royal Navy found itself in the dock over its system of courts martial which was still stuck in the past. The European Court of Human Rights ruled that naval courts martial failed to guarantee defendants 'a fair hearing by an independent tribunal'. Unlike in the Army and the Royal Air Force, naval courts martial were presided over and advised on points of law by senior serving officers who could be subject to pressure within the Service rather than by qualified civilians appointed by the Lord Chancellor and beyond the possibility of being disciplined or compromised. The Court held that civilian appointees as court martial president or Judge Advocate were a vital safeguard for fairness and independence.

Share on

Facebook

Share on

Facebook Share on Twitter

Share on Twitter Share on

LinkedIn

Share on

LinkedIn Share on

WhatsApp

Share on

WhatsApp Copy

link

Copy

link