Tribute to Walter Kendall (1926–2003)

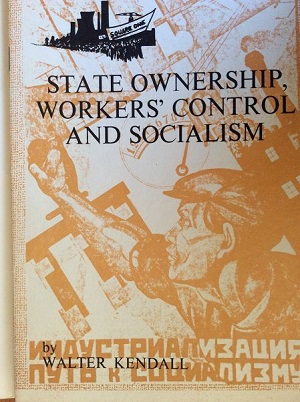

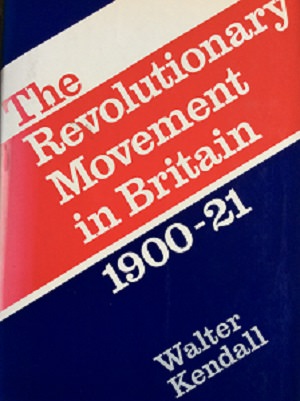

I first became aware of Walter Kendall, the editor of Voice of the Unions and member of the executive committee of the Institute for Workers’ Control, when I was living in Ottawa and working for the Canadian labour movement. He was then a Research Fellow in the Centre for Contemporary European Studies at Sussex University. When I registered for post-graduate work at Sussex, he took an interest in my research for an M Phil on rank and file movements and workers’ control in the British engineering industry. He was just about to publish his path-breaking study of the foundation of the British Communist Party (The Revolutionary Movement in Britain, 1900–21, Weidenfeld and Nicolson, 1969) and would soon start work on a major book on the labour movement in Europe (The Labour Movement in Europe, Allen Lane, 1975). These books earned him an international reputation as a scholar. In these same years, he was elected chairman of the Society for the Study of Labour History in succession to Eric Hobsbawm. In these various roles, he had a major influence on me and I got to know him well.

He encouraged my research on the internal governance of European trade unions, which was later published as Democracy and Government in European Trade Unions. He introduced me to Commander Harry Pursey, a former “ranker” officer in the Royal Navy and retired Labour MP, who, as an able seaman, had been a member of the movement for reform of lower-deck conditions pre-1914, and whose personal archive was invaluable in helping me to complete my D Phil thesis on the interface between naval radicalism and the labour movement – subsequently published as The Lower Deck of the Royal Navy 1900-1939: Invergordon in Perspective. But it was as a labour movement activist that I knew Walter best of all, working with him on the editorial board of Voice of the Unions where we shared a concern for the democratisation of the labour movement and the pursuit of workers’ control in industry.

As a libertarian socialist and internationalist, Walter made an important contribution to the radicalisation of the British labour movement from the 1960s to the 1980s. In 1963 he helped establish the monthly paper, Voice of the Unions, as a forum for rank and file opinion. Its primary focus was on the then-forgotten issue of workers’ control. Within five years it helped pave the way for the Institute for Workers’ Control (IWC) and nudged the Labour government of Harold Wilson towards early experiments with industrial democracy. Delivering the opening address to the founding conference of the IWC, Kendall insisted that Wilson’s Labour government had run out of steam: the policy to re-energise it was workers’ control.

Under Kendall’s editorship, Voice of the Unions and its industrial spin-offs – particularly Engineering Voice, which played a key role in securing the election of Hugh Scanlon as president of the Engineering Union – campaigned for a greater trade union emphasis on workers’ control, going beyond mere money-wage militancy. “Our aim is not to bake a bigger cake, or obtain a bigger share of the cake”, Walter would say, “we want control of the bakery.”

Though he was a serious scholar, he spent relatively few years immersed in academia – two fixed term spells at Sussex as Senior Research Fellow, a similar appointment at Nuffield College, Oxford, and visiting professorships at Wayne State University, Detroit and Trinity College, Dublin was all. He simply wasn’t interested in the academic “game”. As a genuine working-class intellectual, he regarded teaching and activism as opposite sides of the same coin and he was most at home teaching politics to trade union students at Ruskin College, the workers’ college at Oxford, and on extra-mural courses for workers generally. He aimed to have an influence at the most practical level; characteristically, his hope for The Labour Movement in Europe was that it would “help to introduce across national frontiers the workers and intellectuals of each nation to the other.” It’s interesting to see how he reached this position.

He was born into a working-class family in London’s East Ham, leaving school towards the end of the war – “joining the ranks of organised labour” as he would say – to work as a clerk in the Ministry of Economic Warfare. For the next ten years he held a succession of clerical jobs. The year 1948 found him working in the PX (American NAAFI) of the giant US Air Force base at Burtonwood in the north of England where, as a twenty-two year old member of the Transport and General Workers Union (T&GWU), he led his first strike in the course of organising warehouse staff.

Unfortunately for Walter, this was at the height of the Berlin Airlift. Burtonwood was the USAF’s main service and maintenance depot for planes flying to Germany, and he found himself up against not just the US Air Force but also the T&GWU leadership who pulled the plug on the strike by refusing to make it official. Walter was hung out to dry and management cashiered him to a new job in remote part of the base. He drew the appropriate lesson, looked for work elsewhere and quickly transferred his loyalty to the Union of Shop, Distributive and General Workers (USDAW), to which he belonged for the rest of his life.

In the following years, he became a leading left-wing rank and filer, a prominent speaker at USDAW annual conferences and a regular union delegate to Labour Party and TUC conferences. He led a campaign to link union recruitment to militant wage bargaining that targeted the super-stores at the expense of traditional national minimum wage negotiations. USDAW’s general secretary threatened to resign if the policy was adopted, but Kendall’s efforts were successful.

Outside the union, he was a political activist; as a left-wing critic of totalitarian regimes, he made the news picketing outside Claridges during a 1956 visit by Communist leaders Bulganin and Khrushchev and calling for the release from a Soviet labour camp of Len Wincott who had been a prominent lower-deck mutineer at Invergordon in 1931, before going to live in the Soviet Union and subsequently fighting with the Red Army at Leningrad. This was very much the Walter Kendall I knew, the same man who, in the late 1970s, led a press campaign to free from a Soviet “psychiatric hospital” Victor Klebanov, imprisoned for forming the Association of Free Trade Unions.

Meanwhile, he was already contributing to a number of labour movement publications and had begun to delve into the history of the international labour movement to try to make sense of the trade union politics he experienced in the workplace. Autodidact though he was, he sought guidance from people like Alfred Rosmer, friend of Trotsky and founder member of the French Communist Party and Comintern, and also former Italian Communist Party activist Giulio Seniga. Walter grew frustrated at restrictions on his scope for study, so in the late 1950s he quit a steady clerical job with a merchant bank to qualify as a London tour guide and so have more flexible hours for his labour movement research in the British Museum. By the early 1960s, without any formal training as a historian, he had produced a draft history of the British revolutionary movement. It was initially accepted for publication and then turned down by Allen & Unwin on the grounds that his lack of academic qualification would prevent sales.

That was the stimulus for him, aged thirty-six, to seek a place at Ruskin College on a Labour Party scholarship. From there, he went on to Oxford University, gained exemption from doing a first degree and wrote a thesis on the establishment of the British Communist Party for a B Litt. It was the core of what would later appear as The Revolutionary Movement in Britain. In it he argued that British Communism – so heavily influenced from the outside by the Comintern – caused lasting damage to an earlier, native revolutionary tradition, and as such proved a disaster for British workers.

The book attracted much praise, but also bitter criticism in Communist Party circles. Yet Kendall was tireless in his efforts to publicise the cause of workers living under dictatorships seeking to organise themselves independently of state or party control. He believed in human liberty, human dignity, in the right of all people to control their own destiny free from oppression or exploitation. Crucially for him, there could be no economic democracy without political democracy

From the late 1970s he worked on an ambitious study of the baleful influence of the Comintern on national labour movements, provisionally entitled World Revolution, the Russian Revolution and the Communist International, 1898–1935. By now he was increasingly afflicted by ill-health, and when the Soviet archives were eventually opened, he was in no physical condition to avail himself of this corroborating material. His book was unpublished but the typescript is on deposit at the British Library and the Nuffield College Library, Oxford. His personal papers are housed in the International Institute for Social History in Amsterdam

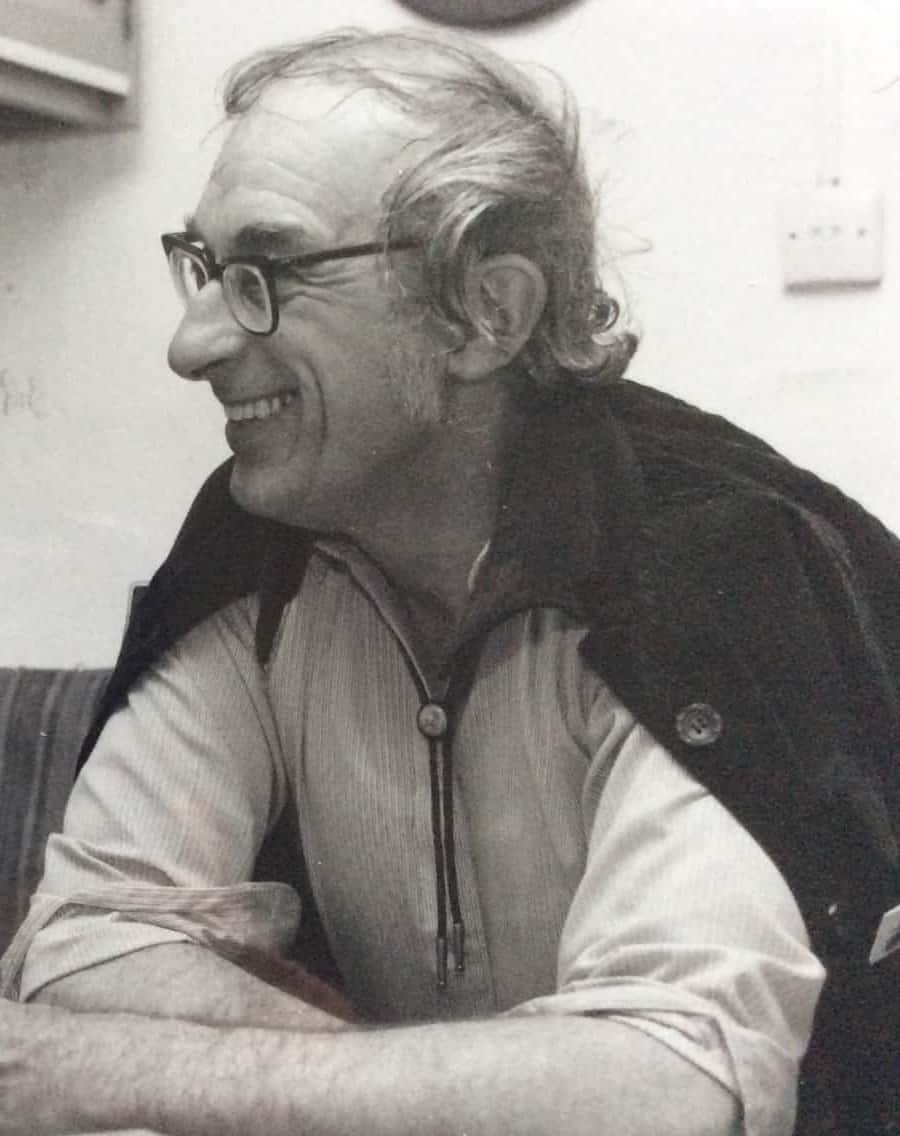

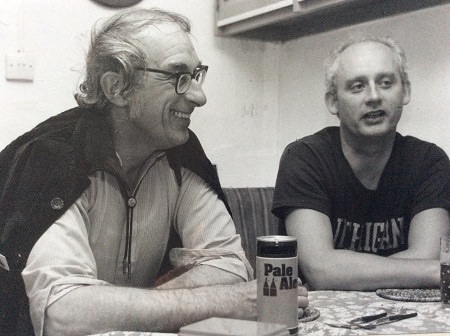

Outwardly extrovert, Walter was, in reality, a very private person, on his guard with strangers and opening up only to a few friends. He was single-minded in advocating his views on democratic socialism and revolution and he made enemies where a more emollient character would not have done. Indefatigable, determined and occasionally difficult, but mostly with a great sense of fun, his optimism would shine through. At the darkest times he would quote Oscar Wilde: “look down and you see the gutter, look up and you see the stars.”

At the end of his life he recalled the strike he had led at Burtonwood, reflecting on the irony that, but for the intervention of T&GWU officialdom, he might have seriously disrupted the Berlin Airlift and so, possibly, the entire course of the Cold War – a wicked thought that elicited Walter’s unmistakable chortle.

See entry and list of Kendall’s writings in Ian Bullock and Anthony Carew, “Walter Frank Harrison Kendall, 1926-2003” in Keith Gildart and David Howell (eds), Dictionary of Labour Biography, vol xiii, Palgrave 2010.

Share on

Facebook

Share on

Facebook Share on Twitter

Share on Twitter Share on

LinkedIn

Share on

LinkedIn Share on

WhatsApp

Share on

WhatsApp Copy

link

Copy

link