Unions in the Industrialised World

Hello. I'm Tony Carew. Welcome to my blog, which I hope you'll enjoy and find informative. It's about my long standing interest in the history and development of organised labour, particularly in its international context. You'll find my outline biography on the About page and links to my work in the additional + menu on mobiles and in the sidebars on larger devices.

The need for

Trade Unions

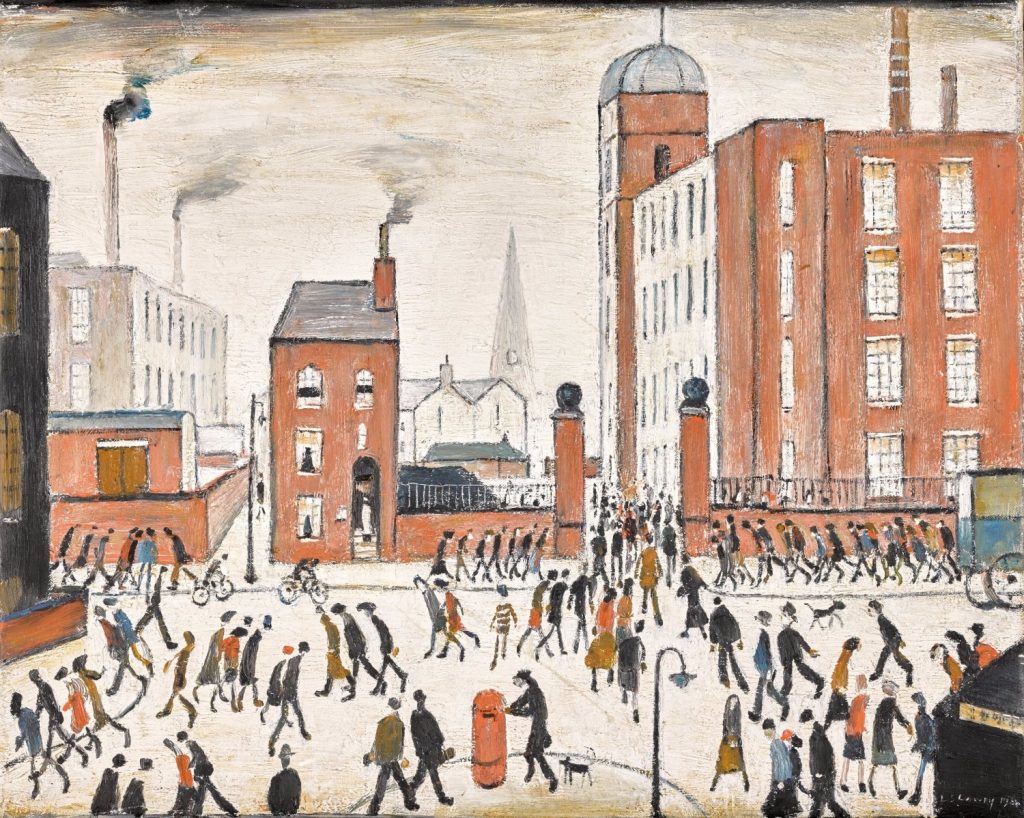

Given my working class family background and upbringing in an archetypal English industrial town, it was always obvious to me that collective organisation by workers in trade unions was indispensable. The evidence of necessary past struggles to improve conditions was all too visible.

The developing

Structures

But trade unions were never homogeneous and interchangeable, and as I became active in the movement, their multi-faceted nature intrigued me. They were craft based, or industry-wide in scope, and increasingly a mixture of the two – indeed “general” in composition and open to almost anyone who cared to join. Such polyglot unions are now the norm. Their structures often told a story of how they had originally come into being, of their inner cultural values, attitudes to democracy and styles of leadership.

The different methods of

Control

Some organisations emphasised the essential need for rank and file control, with elaborate systems of checks and balances on those who aspired to lead. Others veered in an opposite direction, dominated by charismatic, boss-type leaders who emphasised the need for the union to be more than a vehicle for the practice of rank and file democracy. They needed to exercise the discipline essential to winning tangible gains. Such issues are reviewed in my book, Democracy and Government in European Trade Unions, (Allen and Unwin) (1) which draws contrasts and parallels between systems of trade union structure and governance in the unions of what was then the European Economic Community.

Union leadership - the

Reuther Model

“Leadership” is a central theme in my biographical study of Walter Reuther (Walter Reuther Manchester University Press) (2) who, as President of the United Auto Workers (UAW) was one of the most interesting and significant figures in the American labour movement of the post-war years. He embedded socially progressive values in UAW policy and spoke rhetorically of empowering workers, while presiding over a union that imposed firm discipline from top to bottom. In the wider American labour movement, heavily influenced by a tradition of conservative “business unionism”, Reuther presented himself and his union as a radical alternative. Yet on this claim, the gap between appearance and reality is a matter of on-going debate among those who consider his legacy.

International variations in

Philosophy

The “limits and possibilities of trade unionism” was a frequent topic of debate in the 1960s and 1970s when militancy was on the rise in many countries after years of relative quiescence. Mostly the discussion focused on the relationship between trade unionism and politics in socialist theory. Highlighted here were differences in ambition and the end goal of the workers’ movement. Was the purpose simply to secure a bigger share of the “cake” or to transform the world of work? And if the latter, were unions or political parties the best placed to achieve it? In this debate, the orientation of the dominant, communist-led unions of, say, post-war France and Italy, appeared in stark contrast to the more narrowly prescribed goals of American business unions or Japanese enterprise unionism. Such differences inform much of the discussion in my study of American labour’s work abroad in this period, American Labour’s Cold War Abroad: From Deep Freeze to Détente, (Athabasca University Press) (3).

Labour organisation in

The armed forces?

I also examine this issue in what is arguably the most unlikely of situations – that of trade unionism in the armed services, where “common sense” holds that they have no place. In The Lower Deck of the Royal Navy, 1900-39: Invergordon in Perspective, (Manchester University Press) (4) I describe the way ratings on the lower deck of the Royal Navy attempted to improve their conditions of service and to inject an element of democracy through the agency of quasi trade unions in their dealings with authority in this hidebound, disciplined service. These efforts eventually failed, but not before denting in no small way widely held expectations of what could and could not be achieved. The book also provides a case study of the Invergordon Mutiny and challenges what is essentially a Leninist assumption, that radical leadership in such situations can only be provided by the most advanced, politically literate of activists.

International differences in

Approach

Forms of trade unionism are, in many ways, society-specific and are not susceptible to transfer from one country to another. In occupied Germany in the immediate post-war years, officials of the British and United States trade union movement were heavily engaged in helping to rebuild the German labour movement, with no lack of effort to shape it in their own image. But the highly rationalised German movement that emerged preserved the essentials of a German approach to trade unionism. That German trade unionists subsequently found their own, distinctive voice in the international labour movement came as a particular disappointment to some leaders of US unions who had invested heavily in helping to shape their German protégé and now regretted what they regarded as a lack of gratitude. This issue is explored in my American Labour’s Cold War Abroad: From Deep Freeze to Détente (3).

A similar disappointment was experienced by the British TUC, which hoped to bequeath a distinctly British style of trade unionism to their decolonising territories in Africa in the 1960s. African unions rejected the expectation that their unions should develop slowly and organically from the base upwards, preferring a model that began with a national centre focused on nation building rather than sectional workers struggles. This process is dealt with in my contributions “The Trades Union Congress in the International Labour Movement” in A. Campbell, N. Fishman and J. McIlroy, British Trade Unions and Industrial Politics: the Postwar Compromise, 1945-64, (Ashgate) (5) and “The Politics of African Trade Unionism” in A. Carew, M Dreyfus, G. Van Goethem, R. Gumbrell-McCormick and M. van der Linden (ed), The International Confederatiom of Free Trade Unions, (Peter Lang) (6) as well as in my American Labour’s Cold War Abroad: From Deep Freeze to Détente (3).

Influence exerted by the

Marshall Plan

Efforts to influence core values of trade unions overseas were also in evidence during the Marshall Plan years of the late 1940s and 1950s when labour movements in European countries came under sustained pressure to adapt to “the politics of productivity” by accepting what was presented as a superior, modern American trade union approach to the pursuit of productivity growth. Here unions in Britain, France, Italy and Germany were a particular focus of an American ideological offensive. It was a central part of a packet of measures intended to extend the international sway of American business and to shape trade union loyalties in a cold war context. The subject is examined in detail in my book Labour Under the Marshall Plan: the Politics of Productivity and the Marketing of Management Science (7) , (Manchester University Press).

Divisions and the secret

CIA Financing

The intensification of existing international divisions of trade unions from one another – essentially between "free" trade unions and unions within the Soviet camp – was an obvious consequence of the developing Cold War. "Free trade unionism" adopted by the International Confederation of Free Trade Unions as a defining concept highlighted certain aspirations concerning the freedom of trade unions from party, state or church and their right to be self-governing. But it also posed a challenge to solidarity within the ICFTU when affiliated unions chose to exercise that right by maintaining a dialogue with labour groups in other western countries led by communists or with eastern bloc unions – all in pursuit of détente. By the same token, the basic principles of free trade unionism were undermined by trade union acceptance of finance from government in the conduct of specific government-approved foreign programmes. Most significant of all, the extensive and secret CIA financing of American trade work abroad, described in detail in American Labour’s Cold War Abroad: From Deep Freeze to Détente (3), undermined the moral authority of free trade unionism and contributed at a fatal schism in which the AFL-CIO withdrew from the ICFTU.

Increasing the relevance of

International links

International trade union cooperation is conceptually a simple extension of the basic union instinct for solidarity. Yet in practice it often appears as an esoteric subject beyond the reach or ken of rank and file members, conducted by a high priesthood of footloose specialists and multi-linguists. This was an aspect that Walter Reuther, for one, understood and sought to overcome through a deliberate policy of involving rank and file leaders in overseas programmes. In so doing, Reuther won the support of trade unionists overseas otherwise dispirited by the AFL-CIO’s obsessive anti-communism, which acted as brake on efforts to generate a more vibrant trade union internationalism. His efforts in Italy, Japan and Latin America more generally during the years of the Cold War are a particular focus of the biographical study, Walter Reuther (2) and American Labour’s Cold War Abroad: From Deep Freeze to Détente (3).

Likewise, Reuther was also prominent among those insistent on bringing international trade union practice down to a level at which it had more immediate relevance to the base by building international union structures within transnational companies whose key participants were from the unions on the ground rather than the national centres at the apex of the movement. The relative importance of International Trade Secretariats (as they were called) over global internationals such as the International Confederation of Free Trade Unions is the subject of an on-going debate in labour circles and is discussed in A. Carew, M Dreyfus, G. Van Goethem, R. Gumbrell-McCormick and M. van der Linden (ed), The International Confederation of Free Trade Unions, (Peter Lang) (6) and my American Labour’s Cold War Abroad: From Deep Freeze to Détente (3).

- 1. Democracy and Government in European Trade Unions

- 2. Walter Reuther

- 3. American Labour’s Cold War Abroad: From Deep Freeze to Détente

- 4. The Lower Deck of the Royal Navy, 1900-39: Invergordon in Perspective

- 5. Anthony Carew, “The Trade Union Congress in the International Labour Movement”, in A. Campbell, N. Fishman and J. McIlroy, British Trade Unions and Industrial Politics: the Postwar Compromise, 1945-64

- 6. Anthony Carew, Michel Dreyfus, Geeert van Goethem, Rebecca Gumbrell-McCormick and Marcel van der Linden (ed), The International Confederation of Free Trade Unions

- 7. Labour Under the Marshall Plan: the Politics of Productivity and the Marketing of Management Science

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on Twitter

Share on Twitter Share on LinkedIn

Share on LinkedIn Share on

WhatsApp

Share on

WhatsApp Copy

link

Copy

link