John Saville 1916-2009

When I graduated, Saville encouraged me to take a research position with the Canadian labour

movement.

Years later, when

I moved back to Britain, he gave further encouragement to my work in the academic field, first at

the

University of

Sussex and then at the University of Manchester Institute of Science and Technology. It was a proud

moment for me when I

appeared on the same panel at the North American Labour History Conference in 1995. So I owe a great

deal to him and to

the Economics Programme at Hull, and I regard my recent book, American Labour’s Cold War

Abroad, written

in retirement,

as a personal tribute to Saville.

Key Figures on Campus, University of Hull Alumni Newsletter, October 2018

John Saville Remembered: A Personal Tribute – Anthony Carew

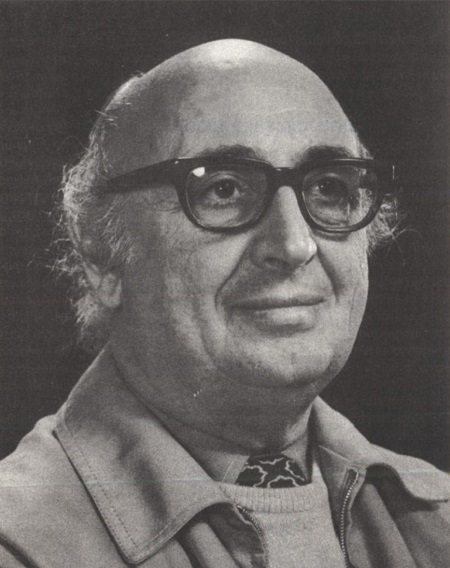

“I’m John Saville”, he announced to first-year economics students in his no-nonsense way. He had been a gunnery sergeant during the War, and now in October 1961 he sounded like a sergeant addressing nervous teenage recruits.

In his mid-forties, he was of medium build, with an owl-like face and sharp eyes behind heavy-rimmed glasses. Above was a bald dome with darkish hair to the sides and rear where it tended to grow over the back of his collar. Before long hair became fashionable, it suggested a lack of interest in his personal appearance.

“I’m a mister”, he went on. “In universities there are professors, doctors and misters, and I’m a mister”. It was my first exposure to academic hierarchy and he was making an important point about parity of esteem. What counted was competence in the lecture theatre and quality of scholarship rather than any formal title. It went hand in hand with his disdain for flummery: he neglected to wear an academic gown in days when not only lecturers but also students were supposed to wear them.

We students rated him our most interesting and engaging lecturer. No hand outs or visual aids: it was just him talking. Rarely consulting his notes, his delivery was never rushed, the tone almost conversational. Yet he never lost his thread or diverted from the main theme, which always developed clearly.

“Let me paint the background”, he would say. This polite use of the imperative was a trademark feature of his rhetorical style. “Listen carefully to me”, he seemed to be saying, “I am now going to make it all crystal clear.” It was the reassuring approach of a lecturer thoroughly on top of his subject and totally confident of his ability to reach his audience.

I was fascinated from the outset, and transferred to Saville’s economic-social-labour history special options at the first opportunity. These were less formal affairs – a mixture of seminar and impromptu lecture held in an office crammed with books on the ground floor of what is now the Venn Building. Saville sat behind his desk while eight or ten students squeezed in around the walls. No one ever missed a class: we felt we were learning from a genuine authority. Transferring to his options was the single most important academic decision I took while at Hull. Indeed, it determined the direction of my adult life.

Well-known for his “new left” radical politics, he was the object of great fascination among students. A former communist, together with E.P. Thompson he had founded the New Reasoner which later metamorphosed into the New Left Review. In my days at Hull, he was making plans for what would later become his edited annual Socialist Register and was also beginning to embark on the monumental Dictionary of Labour Biography that he edited for many years.

![A document produced by Communist Party of Great Britain on the subject of Saville and E.P. Thompson’s activities surrounding the publication of The Reasoner in 1956, held at the Hull History Centre [U DCP]](images/u-dcp-1jpeg-min_400.jpg)

His politics informed his teaching, while on campus he was ever willing to engage in political debate. At a student union meeting addressed by Max Mosley, son of the British fascist leader Oswald Mosley, Saville attended and, in an atmosphere that was almost electric, weighed in and tore Mosley’s contribution to shreds. In academia more widely, Saville was well known as leader of the Campaign for Academic Freedom and Democracy, which took up the cudgels for academics (mostly junior staff) who were being victimised for their political views. In this forum, Saville could be a devastating advocate.

His historical analysis of the de-radicalising influence of the “special relationship” with America on British labour politics jibed with some of my subsequent research. Thirty years after I left Hull, I found myself speaking alongside him on this broad theme at the North American Labour History Conference in Detroit. For me that was a special moment.

A book on American Labour and the Cold War was then germinating in my mind. Twenty-two years on it has recently been published and I’m just sorry that John Saville isn’t around to review it. But I’m clear in my mind that its origins go back way beyond our appearance together in Detroit – in fact, to that initial eye-opening contact as a fresher in October 1961. My book is my personal tribute to him.

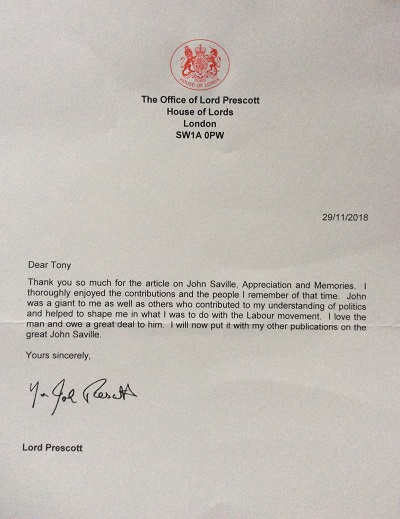

Further Tributes to John

LORD PRESCOTT

JOHN KENNEDY

(Economics 1964)

November 5, 2018. Many thanks to Anthony Carew for his article on John Saville. I can only confirm Anthony’s views – we shared the same experience, as I attended the Saville seminars with Antony. John Saville was an inspiration…..one of the best teachers I have known…. who created motivation and enthusiasm amongst all his students.

Share on

Facebook

Share on

Facebook Share on Twitter

Share on Twitter Share on

LinkedIn

Share on

LinkedIn Share on

WhatsApp

Share on

WhatsApp Copy

link

Copy

link